(originally published Oct. 21, 2011)

In his preface to the 1904 Tauchnitz edition of Kwaidan, Lafcadio Hearn explains that most of the stories he retells are taken from old Japanese manuscripts. Some may have had Chinese origins, he suggests, but “the Japanese story-teller, in any case, has so re-coloured and reshaped his borrowing as to naturalise it.”

The unnamed author of the introduction writes: “The Japanese… have possessed no national and universally recognized figures as Turgenieff or Tolstoy. They need an interpreter. It may be doubted whether any oriental race has ever had an interpreter gifted with more perfect insight and sympathy than Lafcadio Hearn has brought to the translation of Japan into terms of our occidental speech.”

Oh, we lucky, lucky Orientals.

*

In fourth grade, my teacher assigned the class to write a Halloween story. I used my brother’s computer, a heat-spewing bludgeon with a black-and-cyan monitor. After seven pages, however, the cursor froze at the edge of the screen, forcing me to go back and wrap up my story quicker. The next day, I discovered that my classmates’ stories hardly went up to two pages. My teacher flipped through my dot-matrixed creation warily.

For me, ghost stories were second nature. I’d read the anthologies in my elementary school library—100 Great Ghost Stories; Tales of the Supernatural—the page edges brown and warped from moist fingertips. I’d come across, time and again, the same Victorian and Edwardian writers: Sheridan Le Fanu, M.R. James, Arthur Machen, Robert Aickman, Walter de le Mare, Algernon Blackwood. (Lafcadio Hearn must surely have been among them.) I absorbed the stories, ingested the prose until the word ‘eldritch’ became part of my every day speech.

And yet, my story read like a collection of horror movie clichés: full moon; someone impaled on a television antenna; tame gore; someone falling into an open grave. I wonder now: what had happened to those eminent Victorians?

*

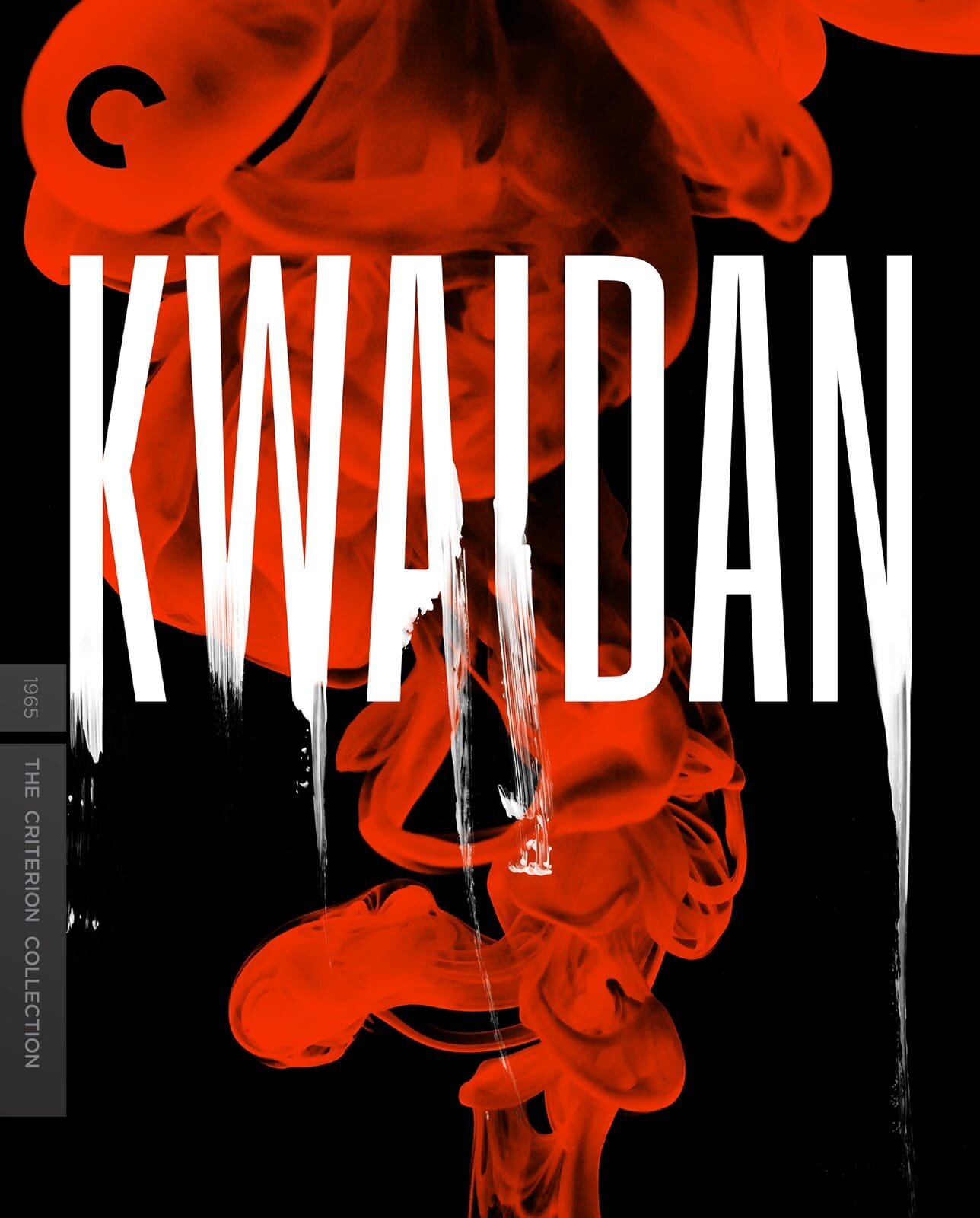

The final segment of Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan, “In a Cup of Tea,” comes not from Hearn’s Kwaidan, but instead from Kottō: Being Japanese Curios. In introducing his story, Hearn relies on classic Gothic imagery (“Have you ever attempted to mount some old tower stairway, spiring up through darkness, and in the heart of that darkness found yourself at the cobwebbed edge of nothing?”) before starting his narrative. But the story itself is incomplete: Hearn ends the fragment with an ellipsis. “I am able to imagine several possible endings;” he writes, “but none of them would satisfy an Occidental imagination. I prefer to let the reader attempt to decide for himself the probable consequence of swallowing a Soul.” Kobayashi, for his part, ends his film by showing the story-writer himself, trapped in a cistern of water, as if to suggest that this is the answer: one becomes what one consumes.

Did Lafcadio Hearn disappear into a cup of green tea for swallowing the Japanese soul?

Will I disappear into a pot of orange pekoe?

I am able to imagine several possible endings, but none of them would satisfy an Occidental imagination.