In a long sequence in Jacques Becker’s Le Trou, we watch prisoners—men who neither protest their innocence nor speak about their crimes—struggle to dig a hole in their shared cell, using the makeshift tools they have at their disposal: a periscope fashioned out of a toothbrush and a mirror shard to track the movements of the guards; a weighted rope to transfer items from one cell window to another; a metal bar from the bedframe to serve as a crude hammer to break through the floor in what feels like an unbroken scene, though in truth, there are a number of cuts, most notably to shots of the men’s faces, staring anxiously, impatiently, worried that they will be discovered, at times mumbling wordlessly, even though the sound of the metal bar pinging against the concrete is ostensibly covered by the sound of construction elsewhere in the prison, but the noise is so incessant that one of the prisoners clasps his hands over his ears, but that metal bar that becomes the focal point: striking the concrete with what seems like futility—a few white specks, like dots of chalk on a chalkboard, until—amazingly—a chip flies away, and then a crack appears, and in aching slowness, the crack widens, the result of the pure, continual effort that the men have exerted; it seems like real concrete that they are trying to break through, a piece of cloth around the metal to protect tender flesh from friction, and I wonder if all work is like this, furious pounding against a concrete floor, progress measured in crumbs, in shards, in exertion, and how this notion is forced upon us, how we imagine freedom to lie on the other side of that work, how even in prison these men are expected to work assembling cardboard boxes, and how this work facilitates their real work of escape, how they dig into the floor, breaking rocks into smaller rocks, and smaller rocks into dust, scooping it away in small tin pots and transferring it into cloth bags until they have broken through the floor and into the space below, a darkness illuminated by burning cardboard, and even so, the men show no excitement at their progress, at what they’ve accomplished, they take no time to admire their efforts, a hole large enough to disappear into, like a momentary release from routine, and in truth, the men know that, soon enough, the process will repeat, there will be another wall to break through, there will be more debris to clear, there will be more aching muscles and more stiff knuckles, and all this will be undone by one feckless co-worker seeking the easy way out, and I think, Yes, that’s exactly what work is like.

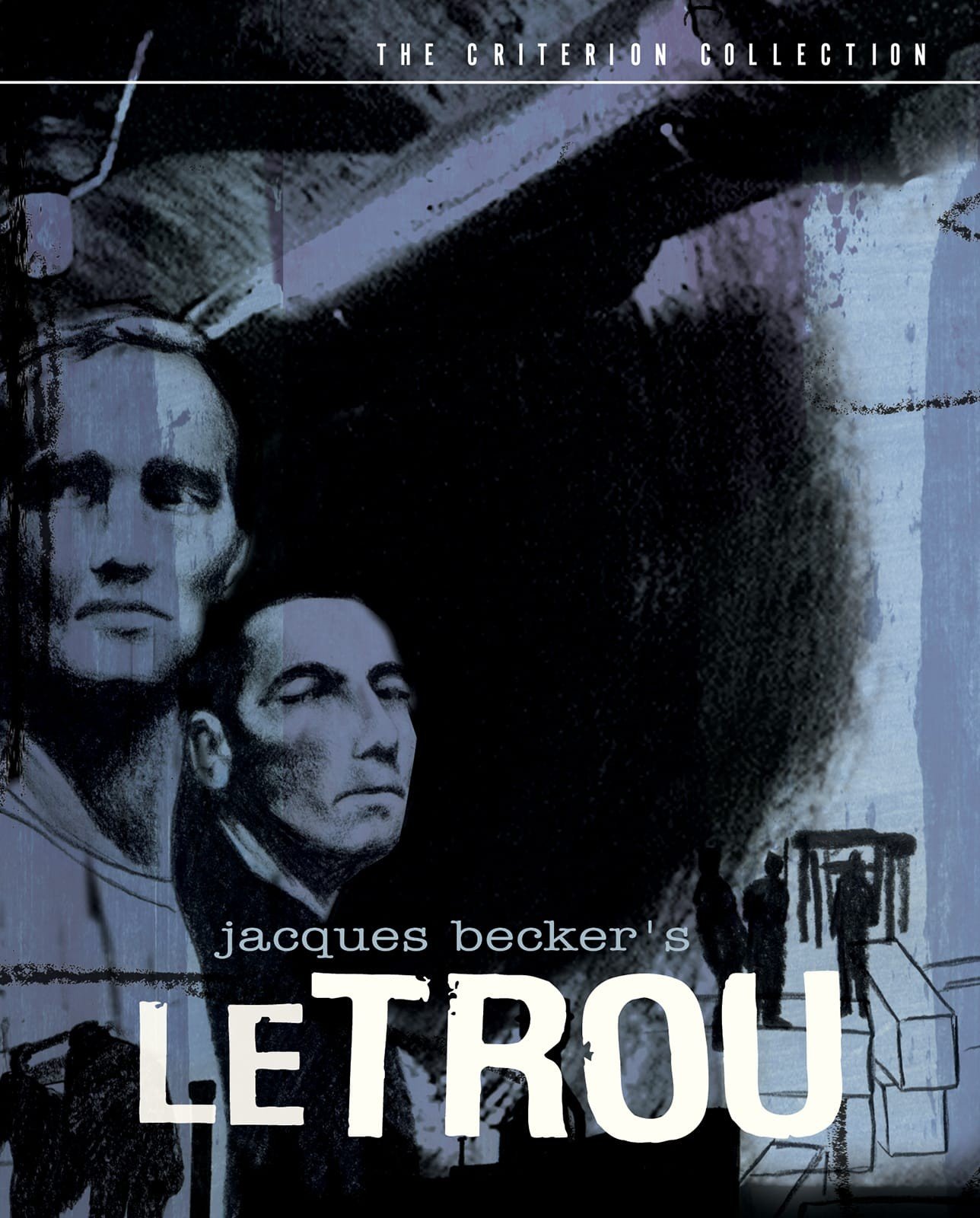

Jacques Becker