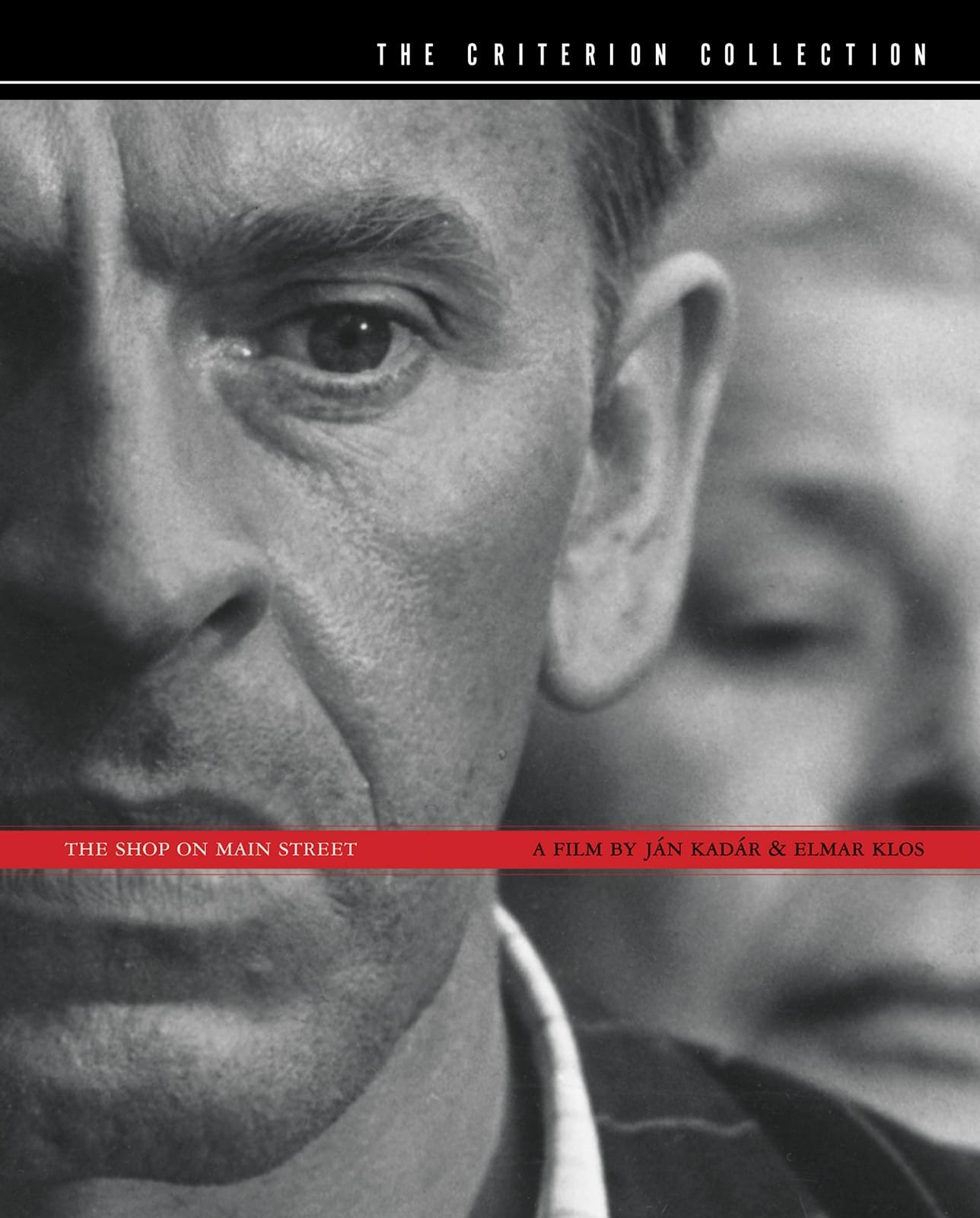

On Main Street, Newark, Delaware, is a tailoring and alterations shop called Italo’s. It sits above a coffee shop that has gone through at least three iterations; Italo’s remains unchanged, its interior carpeted in the drab corporate beige engineered to suck away stains and personality alike. It swallows pins and staples. The shop fits one customer at a time, a counter cutting off access to the workspace and the windows that look onto the drunken students parading down Main Street. Its sign seems unchanged from the 80s: the shop name, a clip art needle, a clip art sewing machine. Italo’s is run by Dan, who, as I understand it, was once employed by Italo himself and simply kept the name when Italo retired. In The Shop on Main Street, Tono acquires his shop by fiat—the Aryan ‘comptroller’ of a Jewish business; this seems to be the direct inverse: a minority business owner taking over a previously Anglo business.

Dan reminds me of my father—they are both Vietnamese immigrants. A generation of men who kept their heads down and worked, trying their best to pass on that lesson to their children, who absorbed them to varying degrees. Dan has taken up sleeves for me, hemmed pant cuffs, taken in jackets and, more recently, let out waists and seats. He’s done well for himself; his racks are always filled with fluffy prom dresses, suits sharp and pressed, shirts dangling like lost skin. He chalks the cloth with deft, definitive strokes; his hands will one day be my father’s hands, I think: puffy, weakened by brain swelling, a tumor pushing away the able-bodied man I remember. My father’s unable to hold a pair of chopsticks and uses silverware awkwardly with his left hand, as his right can no longer grasp even a pen. Dan has shifted to being open only part-time, in preparation for his own retirement. My father retired decades ago. Rozalie, the owner of the button store in The Shop on Main Street, never retires, but instead keeps her store open with no inventory, buoyed only by the Jewish community, under threat by the authorities.

There’s a handful of other Vietnamese businesses on Main Street: a bánh mi shop, and a phở restaurant owned by Koreans. The community in Delaware isn’t big; you’d have to go to Philadelphia to find significant numbers. But I hear snippets of the language while wandering through Costco; I get a moment of wide-eyed surprise when I order at the Vietnamese restaurant owned by actual Vietnamese a few miles away. I rarely see other Vietnamese people in there. I took my father there once when he was visiting me in Delaware; he declared the food ‘acceptable.’ He rarely eats anything except Vietnamese food, which, in his old age, I suppose he sees as his right. He’s too weak to leave his house in Colorado, and so I bring home take-out when I visit.

No one is coming for us, so we show up for ourselves.