(originally published Jan. 5, 2012)

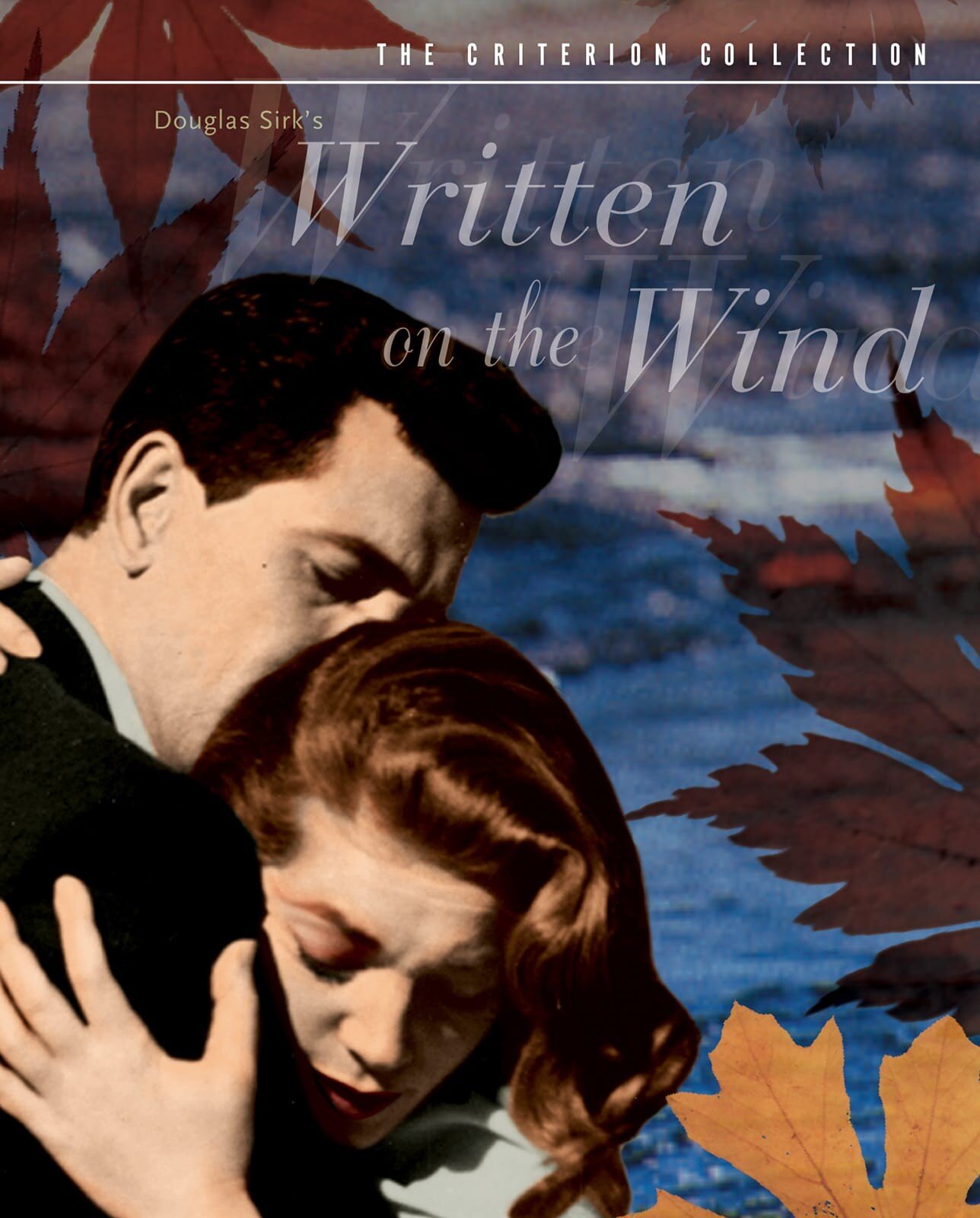

Opening shot of Written on the Wind: a sports car races across a barren Texan landscape. Oil derricks rise out of the ground like metallic spines, upright. The sky is a blue that exists only in the movies—a day-for-night shot—bright as electricity, deep as evening, and the starkness of the sky makes you think that Texas is always like this: empty, endless, illuminated.

When I was young, my father brought home magazines from his visits to our local HMO. National Geographic for him; Reader’s Digest for my mother; Ranger Rick for me. I asked him to buy me a subscription, but he said no, that these copies with the address label ripped off were good enough. One issue I recall featured pictures of the decorated pumpjacks in Luling, Texas. They struck me as odd and beautiful, how they simultaneously mimicked nature and denuded it. One was a smiling Monarch butterfly, its wings attached to the pump arm. Another was made up as killer whale; the third, a zebra. My brother had just started his degree in petroleum engineering at the Colorado School of Mines. He would, I thought, soon be working with these strange creatures.

Douglas Sirk describes the oil well as “a rather frightening symbol of American society,” a symbol of emptiness, of loss. Rainer Fassbinder points out how the golden miniature oil rig that the scion of the family holds in his portrait “looks like a penis substitute.” The presence of oil is ubiquitous: after Lauren Bacall discovers she’s pregnant, she leaves via the back alley behind the doctor’s office, and, in the upper-left corner of the frame, a grasshopper-green oil pump drains the parking lot.

After graduation, my brother got a job with Atlantic Richfield Company in Midland, Texas, and, for a while, my parents only bought gas from Arco stations on the assumption that they were somehow supporting him. One summer, the family piled into the van to pay him a visit. I remember the long stretches of flat, empty road, where land just seemed to fall off the horizon. From afar, the oil derricks looked like spindly saguaros, and it wasn’t until we got close that I could see their exoskeletons. If it weren’t for them holding the state down, it seemed, Texas might have just blown away.

The final scene of Written on the Wind, as described by Fassbinder: “Dorothy Malone, as the last remnant of the family, has this penis in her hand…. The oil empire that Dorothy now heads is her substitute for Rock Hudson.” Oil, the film suggests, is no substitute for life.

Of the three siblings in my family, my brother is the ‘successful’ one. He works for BP and flies to Aberdeen, Scotland, to plan where to plant off-shore oil drills off the Vietnam coast. He owns a large house just outside of Houston (just being about an hour’s drive), where he lives with his wife and daughter. His wife, who also went to the Colorado School of Mines, also works in petroleum. My parents constantly (still) worry about my sister and I, but him—his life is set.